Edition 2 Newsletter By Maria Ganci

August 2023

Clinician Question

“How can I help parents to respond emotionally in a more appropriate way and how can I teach them.”

Your Emotional Response to your Adolescent

It’s important to help parents understand how their own emotional responses impact their own mental state and the impact on how they manage the treatment. Educating parents if the key by explaining the following

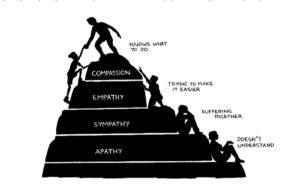

Let’s do a quick review on the four emotional ways parents respond to their child: apathy, sympathy, empathy, and compassion. This will help you identify how they respond.

Apathy

Apathy

At the bottom there is apathy. Apathy means that you are disconnected from what is happening. Parents usually respond this way very early on in the life of anorexia. At this stage, they are unfamiliar with the impact of anorexia; therefore, struggle to understand what’s really going on for their adolescent. Apathy is evident when you hear parents say, “Why don’t they just eat?” or “How hard can it be to eat, they are just stubborn.” Responding with apathy gives your child the message “I don’t understand what’s happening to you.” “I’m not connected to what you are feeling.”

Sympathy

Parents usually have a lot of sympathy because they love their adolescent. Seeing them struggling at meals and becoming distressed at meals usually results in too much sympathy. Sympathy actually means “suffering together.” Too much sympathy won’t get your child healthy. The message you give with sympathy is, “I feel so sorry for you, and I understand how hard this is for you that I just can’t make it any harder for you by challenging the anorexia, so I am not going to insist that you eat everything you need to eat. I will just sit with you and share your suffering with you.” If your only response is sympathy both you and your child will be stuck. Your child will remain in the grips of anorexia as they cannot fight it on their own.

Empathy

Then we move to empathy. Empathy is a wonderful and important social emotion. Empathy allows us to understand cognitively and emotionally how the other feels. It is only when we are able to empathize that we have the capacity to truly connect with others.

Empathetic parents understand how difficult eating is for their adolescents. They understand the impact of the distressing AN cognitions. The adolescent also feels that their parents understand their difficulty and distress. Unfortunately, empathy becomes a problem when parents are so concerned and connected to their adolescent’s distress that they become over empathetic, and it can lead to “empathic distress.” Research highlights that this can occur very easily when caring for a loved one who is in extreme distress.

The definition of empathic distress is when someone overidentifies with the other’s distress and actually experiences it as their own pain—resulting in no distinction between self and other. Your adolescent’s distress is experienced as your own intense pain. Research has shown that when someone is experiencing empathic distress it highlights the areas in the brain that register pain; therefore, the person goes into protective mode by activating the sympathetic nervous system’s flight/fight response in order to avoid the pain.

When this happens parents become disempowered as they feel they cannot change the situation. They can also become so overwhelmed that they struggle to use appropriate strategies and knowledge provided by their therapist to manage the situation due to the prefrontal lobes of the brain (where all the cognitive processes occur) going off-line. Under such circumstances, parents want to make refeeding less distressful for both their adolescent and themselves so they agree to their adolescent’s demands for “light foods” or “safe foods” and smaller portions. This is a very common experience for parents, not only when dealing with a child with anorexia, but in all circumstances when carers deal with someone who is in extreme distress.

Whilst you may see some improvement in your relationship with your child with lots of empathy, both you and your child remain stuck as full recovery becomes unachievable. Full recovery means normalized eating, and this will only occur if your child becomes comfortable eating everything, including all foods that they ate prior to the anorexia. When you are over empathetic the message you give your child is “I understand you and will make this as easy as I can for you at the expense of full recovery.” Parents can become so empathetic that sometimes they will say, “At least she is eating, it is better than not eating at all.” The problem with this view is that you will not free your adolescent from the grips of anorexia to reach her full potential in life.

Compassion

Finally, there is compassion. The research literature on compassion states that it involves four major elements:

- An awareness of the suffering

- A concern about the person suffering

- A desire to relieve the suffering, and

- A commitment or willingness to respond to the suffering, that is, a resolve to eliminate the distress/suffering.

When parents feel compassion, they are aware of their adolescent’s pain and suffering. There is a genuine concern about their child’s distress and battle with anorexia and how their child cannot relieve their own distress without parental support. They also have a desire and commitment to relieve the suffering and understand what they need to do to eliminate the distress.

With compassion, whilst there is a lot of empathy, there is a clear distinction that the pain and suffering belong to their adolescent and it is not their own. Their own distress is out of concern for their adolescent. This clear distinction allows parents to become very effective in eliminating the distress because they do not avoid the difficult things they need to do to achieve recovery. The message you give your adolescent is, “I understand you, and I feel with you, but I am going to get you better. I am going to get you out of that place where you are so stuck.”

Another feature of compassion, as opposed to empathy, is that it uses the reward pathways of the brain and not the pain pathways. When parents respond with compassion, they experience a sense of doing something helpful which is rewarded by the appropriate “feel good” hormones and this increases their feelings of connection to their child and their own values.

Given the intensity of the treatment, parents will swing between these four emotions but ultimately if they are to get their adolescent better they will need to be functioning for most of the time (90–95%). with compassion.